Schneider versus Krupp

|

The

incontestable superiority of the Balkan States in artillery fire gave rise to

a bitter dispute which lasted for some time between the French and Germans as

to the relative merits of their artillery. This was because the allied

armies, with the exception of It was not

only a technical matter, but also, and especially, a political and a business

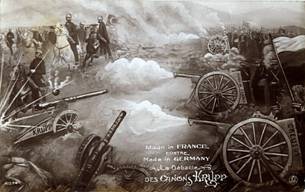

affair. The French press immediately announced with great emphasis that the

disasters which had befallen the Ottoman Army in October 1912 were due to the

weakness of the German weapons and to the faults of the German doctrines. The French

firm Schneider-Canet took immediately advantage of the opportunity. The

promotional postcard reproduced below was printed just after the first

victories of the Balkan Armies, since the copy I have was posted on 9

December 1912. For instance

Henri Barby, war correspondent of the French paper Journal and fervent Serbophile, in his books on the Balkan wars

devoted an entire chapter respectively to the Serbian artillery (La guerrre des

Balkans, pp. 273-287) and to the

artillery during the second Balkan war (Brégalnitsa, pp. 305-314). The conclusion of

his detailed analysis was simple: “The success obtained by the Serbian

artillery during the campaign is the success of the French artillery, since

the Serbian army used only our field and siege materiél. We must ascribe

these successes to the indisputable merits of this matériel and of its

ammunition, to the first-rate training of officers and men, to a system of

fire discipline largely inspired to the French school.” The results got by

the Turks, using Krupp guns and following the “old” German rules, were poor

and ineffective. The Bulgarian

guns, even if similar to the Serbs ones, were less improved, having recoil

system with springs, instead of compressed air running-up gears, and being

not fitted for an independent line of sight. Therefore their fire was less

effective, so that, according with monsieur Barby, Odrin fell only thanks to

the support of the Serbian heavy guns. The superiority

of the French guns was so great, that German military experts were forced to

reply to the criticisms. In November 1912 the German review Militär-Wochenblatt published a brief

article, entirely devoted to the German guns employed during the first weeks

of the war. But the

dispute was limited to The response

was not late. On 28 November The New

York Times published a letter of a certain Tomo Sargentich, who rebutted

“the unfair deduction of superiority of the French Creusot guns over the

German Krupp guns”. His reply was very simple: “The writer is not a German,

but in the interest of truth and fairness ventures to assert his belief that

the Krupp guns, manned and handled by the Kaiser’s artillerymen, are a very

different weapon than the same Krupp guns manned and handled by the

half-starved, wretched and ragged Turkish soldier.” This time too the

conclusion was sharp “it was the men behind the guns – the brave Bulgarians –

that won the day.” Finally on 26

February 1913 The New York Times

published “an authentic statement, emanating

from high Bulgarian official circles… contradicting a widespread general

opinion”. This time the expert was an anonymous Bulgarian officer. In spite

of the common opinion, he emphasized that 75% of the guns, 90% of the

ammunition – even for French material –, and all the fuses used by the

Bulgarian artillery came from Krupp. Moreover he added that, as for methods

and regulations, the But what

differences existed between the Schneider and the Krupp field guns?

Ballistically there was little appreciable difference. Both guns had the same

calibre, However there

were some minor points in favour of the French model. First of all, they had

a different recoil mechanism, which took the shock of recoil from the

carriage, and the “recuperation,” or counter recoil system, which stored up

the necessary energy to return the gun to its position in battery. All the

brakes were hydraulic and utilized the resistance resulting from the passage

of a liquid through narrow orifices. As for the “recuperation,” the Krupp gun

was equipped with spiral recoil springs, the Schneider either with springs ( But it was especially

in the method of laying that the Schneider gun possessed incontestable

advantages. The gun could be moved in azimuth by a sliding of the top

carriage along the axle, as in the French These

advantages were only to a lesser degree in the Krupp gun. The latter,

supported by a cradle, pivoted on a vertical spindle immediately underneath

the middle of the axle and its sighting apparatus was not independent. From

these arrangements it resulted, first, that the recoil had a component

parallel to the axle, which caused derangement of the aim; and, second, that

indirect laying, or masked fire was possible only in exceptional cases.

Finally, the absence of the corrector scale in the Krupp material, and

perhaps the bad quality of the shrapnel fuses, caused significant

irregularities in the time fire. But these defects

were not sufficient to account for the superiority of the Allied armies in

the artillery arm. Rather they had to be ascribed to superior training,

organization, and esprit de corps. The Allies had had their guns for some six

years; drill in occupation of positions, in marching, and in actual firing

had been a part of their training, advantages of which the Turks had had

little or none. |

|

Remark: All the dates

in this page are according the western – Gregorian – calendar. |